Milo Grow’s Letters from the Civil War

Click here for the Letters:

From The Battle of Charleston

(May-June 1862)

The Battle of Fredericksburg

(18 letters, 1862-3)

Letters from Others After Milo Grow’s Death

Introduction

These are the letters of a man caught between divided loyalties. An idealistic northerner educated in the same tradition that produced Emerson and Thoreau, Milo Grow moved south to Georgia shortly before the Civil War, where he taught school and practiced law.

There, he seems to have found a place among the colorful individualists of the small-town South, made friends, developed strong loyalties, and married a spirited woman in a setting where that meant marrying into a whole family, a community, and even a way of life.

These must have been difficult times for a candid, educated Yankee in the deep South. According to historian David Williams in Rich Man’s War, it was a felony in nearby Alabama just to speak out against slavery. Most opponents of slavery had been run out of the region.

The region was profoundly divided about slavery. Many rugged farmers owned a slave or two, around three-fourths of the population owned no slaves, and the majority of the South (including Georgia) opposed secession.

But large planters and slaveholders dominated the economy and the legislatures, and it was not difficult for them to enlist the allegiance of non-slave-owning whites, many of whom seem to have entered the war thinking it would be a brief demonstration of superior Southern spirit and a defense of their independence as a region.

Milo did not enlist at once. In fact, he and his friends volunteered for “the Miller County Guards” only after the draft was declared in 1862. Milo must have been under pressure to enlist–to demonstrate loyalty to his friends and new family, which now included an infant son, and to protect his family from the threat of violence for harboring a Yankee. Also, as Williams points out, enlisting enabled Milo to get a fifty-dollar bonus and choose which unit to serve in.

The draft was not universal. Holders of more than 20 slaves were exempt, and anyone wealthy enough could buy his way out. The Confederate Army seems to have been populated by those with the least to gain from the war. One of Milo’s letters complains that the enlisted men are treated like slaves.

The war was not universally popular in this remote region of the South. In parts of nearby counties, some men never joined the war at all. In nearby Dale County, Alabama, guerrilla bands of war resisters prevented Confederate agents from drafting men, attacked supply trains, and kept circuit court from holding sessions.

Milo’s Northern family reported afterward that he had kept a diary in which he expressed his opposition to slavery and secession (mentioned in Davis, 1913). That diary has not been found.

Milo

Milo Walbridge Grow, writer of these letters, was born at Craftsbury, Vermont, on March 28, 1825, grew up in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, and graduated from Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire.

|

“St. Johnsbury was one of the more strict villages in the mid 1800s. The straight-laced were objecting to the loosening of morals.They did not object to baseball, roller skating, magicians, circus or exhibitions of war panoramas, but they did object to raffles, lotteries or females reading sketches or declaiming in public. –From the Center for |

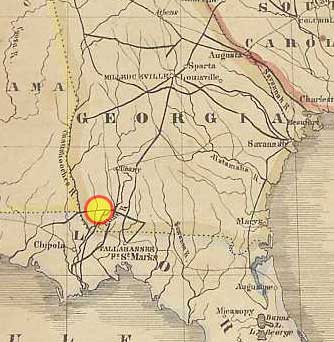

Milo had moved to Georgia by 1853, when he advertised the opening of a school in Albany, Ga.

Milo moved to Colquitt, Georgia in the late 1850s and married Sarah Catherine Baughn on December 13, 1860, in Miller County, Georgia, on the eve of Lincoln’s inauguration and the outbreak of the Civil War.

On December 24, Alabama voted to secede. On January 19, 1861, Georgia seceded. The Confederacy was created in February 1861. Wedding music was quickly followed by the music of war.

Milo enlisted in the Confederate Army, Company D, 51st Regiment, “Miller Guards,” on March 15, 1862. Click here for a sketch of his regiment’s role in the war.

Kate bore their only child–Roy Walbridge Grow, on Oct 31, 1861. Roy was five months old when his father left for the war, not to return.

According to family history, Milo was captured at Gettysburg July 3, 1863, after being wounded the previous day.

He was taken to Fort Delaware, Del., and thence to the new Northern prisoner of war camp at Point Lookout, Maryland, where he died Jan. 24, 1864.

Here is a letter to the editor lamenting the conditions at Point Lookout. Here is a website on Point Lookout. There is an organization of descendants of Point Lookout prisoners. Milo Grow’s name appears in their listing of those who died there.

Milo is buried in the family plot in St. Johnsbury, Vermont.

Kate

Sarah Catherine (Kate) Baughn was born March 19, 1835 in Quincy, Florida, daughter of G. William T. Baughn and Sarah Elizabeth Jarrett Baughn.

At some time after April 2, 1876 (when Mr. Bodiford’s first wife died), Kate married James H. Bodiford and became Kate Bodiford –the name that appears on her grave in Colquitt, Georgia.

In family tradition, she is known as “Mother Bodiford,” and each new baby is knowingly said to have “Mother Bodiford’s chin.”

In the letters, Milo calls Kate by a number of terms of endearment, including Lyra and Lullie. Lyra is the constellation representing Orpheus’ lyre, the mystical source of inspiration. In a touching moment in the winter at Fredericksburg, he describes looking up and seeing Lyra bright in the night sky, no doubt thinking of her.

The only definition of “lullie” given in the unabridged Oxford English Dictionary is “the kidney of a cow.” We can safely assume that Milo had some other meaning in mind.

Some People in the Letters

Uncle Richard: Richard Jarrett, Kate’s brother and a physician. Emory Jarrott of Savannah traced the Jarrott line back to Carteret County, North Carolina, around 1700.

Buly: Van Buren Baughn, Kate’s brother, who later became an attorney and married Martha Sheffield.

Billy: William Baughn, Kate’s brother, who was killed in the Civil War.

Leroy (Lee, Le, Roy, Leetle Lee): Roy Walbridge Grow, Milo and Kate’s son, who later became a Miller County attorney and farmer and married Lou Bush.

Davis: John Davis, 26th District farmer and sheep raiser.

Mrs. Dees: Nancy Dees, tanner and weaver.

Man in regiment who lost his arm: Probably R. W. Dancer, Miller County Ordinary who married Mary Jane Clifton.

Mr. Boykin: Guilford A. Boykin, a farmer and the first Miller County postmaster, who later married Elizabeth Jarrett.

Mr. Anthony: William W. Anthony, circuit-riding Methodist preacher assigned to the Colquitt Charge.

Source: The History of Miller County Georgia by Nellie Cook Davis.

Others connected with the letters

David Grow: Milo’s younger brother, 1829-1879. Identified in the letters as a Mason, David worked as agent of the Jerome Clock Company of New York, spending much time in Europe. Later worked in Chicago with Fairbanks Greenleaf Scale Company, and was manager of the Waterbury Clock Company in New York.

Mila (Lamoille Amanda) Grow: Milo’s sister: b. in Craftsbury, Vt. Feb. 27, 1871. Married Feb. 27, 1871, Charles Woodbury Thrasher (who was born in Cornish, N.H.). They settled in Springfield, Missouri, where he died in 1901. In 1913, Mila and her daughter (Alice Lamoille, b. Sept. 10, 1876) were living in Florence, Italy. Thrasher graduated from Dartmouth, class of 1856, and practiced law. He rose to Colonel in the Civil War. Was nominated for Congress in Missouri, but was defeated. (Lamoille was the name of the adjacent county in Vermont.)

Lamoille H. Grow (born Wallbridge or Walbridge in 1795) was mother to Milo, Mila, an David. Their father, Silas Grow (b. 1795) died August 29, 1862. His will did not leave his estate to his eldest son, Milo, now an enemy soldier. Milo received only payment of the notes that Silas gave for his education. The will also mentions an adopted daughter, Jane Rawson, wife of Horace Rawson of Craftsbury. Lamoille was the name of a nearby county in Vermont.

Milo Grow’s ancestors have been traced back to John Grow of Ipswich, Mass., around 1636.

Source: Taken mostly from John Grow of Ipswich, by George W. Davis, 1913. This book can be ordered from several genealogy sites online, and from UMI, University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346.

To order from UMI, you will need the item number: G-1217.

Publication Data

The text of these letters was compiled by Gerald Grow from Joy Jink’s transcription of the handwritten letters. I have regularized some of the spelling to make the letters easier t read, but left enough to give the flavor of the original. Some of the unusual spellings have a life of their own, like “Leetle Lee.” I added most of the paragraph breaks. Where I was able to obtain the original letter, I checked this text against it.

In a few places, the order and dates of the letters are not clear, so those have been arranged in what seemed a likely sequence.

The hand-tinted photograph of Kate Baughn was discovered by Kaye Dyar among some inherited items in Virginia, with her fading signature on the back and the inscription, “to my only son, Roy Walbridge Grow.”

This edition is copyrighted as a formality to protect it. Permission is freely granted to anyone, however, to reproduce brief excerpts in not-for-profit publications, and to link to this website. Others may contact the editor for permission. Use the Professors/Contact Form at newsroom101.net.

First produced for the Grow family reunion at Lake Seminole State Park, Georgia, Thanksgiving Day, 1986.

A Timeline

At the Grow-Sloan-Jinks family reunion in 2002, Joy Jinks led us in creating a timeline of family history for the past 150 years.

Gerald Grow’s Home Page