An Imaginative Reconstruction of Milo

Grow's experience at Gettysburg

By Gerald Grow, ©1989

|

None of Milo Grow's letters from this period

survived, but family history records that he fought at Gettysburg,

was wounded and captured. Here is a reconstruction of what might

he might have gone through.

Late in the afternoon of July 2, 1863, General Semmes's brigade

was ordered to advance, supporting Kershaw's men. Milo was with

them, in the Georgia 51st Regiment.

Leaving their cover, they advanced into an open field to face

Northern infantry firing from behind rocks and trees. After taking

the field with heavy losses, the attackers fought their way to

a heavily wooded ravine, where they had to drive out the Yankees

rock by rock. Taking the rocks, they faced an open ravine with

a stream at the bottom and rocks providing good cover on the

other side. By the time they crossed it, that stream must have

run red with blood. Then they faced the uphill battle against

infantry firing down from the cover of trees and overhanging

rocks, along a loop of road that jutted out onto the slope. Here,

the fighting must have been bitter and protracted. Monument after

monument marks where Northern forces fought.

Finally gaining the high ground of The Loop, Semme's brigade

faced another nightmare. Beyond their cover of rocks and woods,

a large open field rose to the north of them. Union troops held

it. Union artillery looked down on them from the crest of the

gentle slope of wheat.

In a moment commemorated in the diorama, they charged out of

the woods into The Wheatfield in some of the bloodiest fighting

of the battle. A human wave of men emerged yelling and firing,

against rank upon rank of Union troops, many of whom had breech-loading

Spencer rifles that could sustain a rapid rate of fire.

They took The Wheatfield.

But not for long. The North counterattacked. Back and forth,

North and South crossed the Wheatfield, gaining and losing, surging

and receding. Before the evening came, in that field alone the

scythe of war had cut 6,000 men.

Northern troops pushed back to the far

edge of the ravine, then lost that advantage again. By nightfall,

Semmes's troops held the high ground near the Peach Orchard.

|

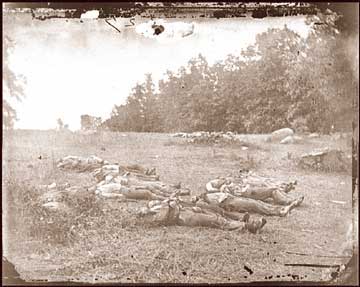

| Confederate prisoners at Gettysburg. (Library

of Congress) |

Among the dying was General Semmes, hit in the ravine and carried

out--according to one story--on a stretcher made of a captured

Union flag. Accounts of that night tell of piercing cries from

the wounded and dying scattered through the woods, slopes, ravine,

and wheatfield. Somewhere among the wounded lay Milo Grow.

The next day, General Lee gambled the war on the single hour

of Pickett's Charge, a heartbreaking carnage of men pressing

up a huge meadow in full view of the artillery at the top of

little Cemetery Ridge. About a mile south of there, by the end

of July 3, Semmes's brigade held the woods along the ravine.

About 1 p.m., the men of Semmes' brigade were ordered to withdraw

to their original starting point on Seminary Ridge (now Confederate

Avenue). They stood in the same field they had started from,

but with what a difference. Of the 1200 in Semmes' Brigade, they

suffered 430 casulties--one out of every three men.

Signs on some of the Northern markers indicate that, during their

back-and-forth fighting, they took prisoners. Near midnight the

next day--July 4, 1863, Independence Day, the same day the North

took Vicksburg--Lee's troops withdrew in a pouring rain. The

South did not have enough wagons to carry their wounded. 2,000

were left behind. Milo Grow was among them.

After Gettysburg, Milo was moved to Point

Lookout, Maryland, the southernmost tip of land on the peninsula

southeast of Washington, D.C. It was the North's only prisoner

of war camp in which the men were kept in tents. There is now

a state park there. Maps show that it overlooks the broad estuary

of the Potomac River and the mouth of the great Chesapeake Bay.

The sea air must have been clean, bracing, and, that winter of

1864, bitterly cold.

|

In this column are excerpts from Civil War songs Milo

probably heard or sang.

Sittin' by the roadside on a summer's day,

Chattin' with my messmates, passing time away,

Lying in the shadow, underneath the trees,

Goodness, how delicious, eating goober peas!

Peas! Peas! Peas! Peas!

Eating goober peas!

Goodness, how delicious,

Eating goober peas!

As long as the Union was faithful to her trust,

Like friends and brethren, kind were we, and just;

But now, when Northern treachery attemps our rights to mar,

We hoist on high the Bonnie Blue Flag that bears a single star.

Hurrah! Hurrah!

For Southern rights, hurrah!

Hurrah for the Bonnie Blue Flag that bears a single star.

A hundred months have passed, Lorena,

Since last I held your hand in mine,

And felt that pulse beat fast, Lorena,

Though mine beat faster far than thine;

A hundred months -- 'twas flow'ry May,

When up the hilly slopes we climbed,

To watch the dying of the day,

And hear the distant church bells chimed.

It matters little now, Lorena,

The past -- is in eternal past,

Our heads will soon lie down, Lorena,

Life's tide is ebbing out so fast;

There is a future -- Oh, thank God --

Of life this is so small a part,

'Tis dust to dust beneath the sod,

But there, up there, 'tis heart to heart.

Hark honor's call, summoning all.

Summoning all of us unto the strife.

Sons of the South, awake! Strike till the brand shall break,

Strike for dear Honor's sake, Freedom and Life!

Strike for dear Honor's sake, Freedom and Life!

War to the hilt, theirs be the guilt,

Who fetter the free man to ransom the slave.

Up then, and undismay'd, sheathe not the battle blade,

Till the last foe is laid low in the grave!

Till the last foe is laid low in the grave!

God save the South, God save the South,

Her altars and firesides, God save the South!

For the great war is nigh, and we will win or die,

Chanting our battle cry, "Freedom or death!"

Chanting our battle cry, "Freedom or death!"

|