|

|

|

Letters After Milo Grow's Death |

|

| When I look at your dear picture I think I can almost see may own dear Wabbie when a little boy, the same expression when he was displeased. |

| It is hard, very hard to bear, tho' the cup is given to us to drink by the most tender and merciful of Beings. The funeral service was very consoling, and I longed for you to share it with us. |

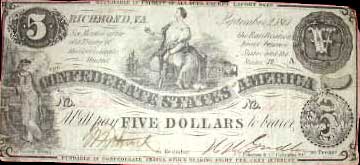

| Confederate soldiers had rarely been paid, and the money they had been able to send home was now worthless. |

| My first sorrow was the loss of my intended, a loss that I realize more and more for he was a noble man. My next sorrow was my Father's death, and the next my brother. Is it not enough? Every part of my heart except the part occupied by my Mother has been torn. And I came near losing her this Spring. |

| Sleep on, I would not have

thee know The fate of one so loved, T'would grieve thy proud and generous heart, Though in the realms above. |

| The more common method, by which genius is acquired, is, when a youth of common talents, aspires to be an instrument of good to mankind.... |

| It requires that stimulus which naught but man, fired with zeal in his subject, can give, to enforce any principle upon the mind of men. |

| Which is capable of doing the greatest injury to society, a bad man while he lives or a bad book which he may leave behind? |

In treating upon this subject we are to compare the effects of a cause which is silent, only known when it is sought after, with a living actor whose every expression and word is everything an influence-- silent, but nevertheless powerful and effectual. In this comparison, we should recollect that either truth or error is by far the most efficient, when in the hands of an enemy the man who can wield them to a definite purpose, in decisive manner. Error when propagated by the aid of books seldom finds powerful suporters who will devote their time or attention to its extention: therefore a book may be purchased and lay upon the shelf for the space of a year, and should it be perused, the convert to its principles will take little pains to extend them beyond his own roof. Whereas the man who is the author of pernicious principles, feeling ambitious for thier extension, and summoning all his energies into action for the purpose, can hardly fail to exert a great influence upon mankind for evil. Paine, by his arguments and unbounded influence, was able so to work upon the minds of his nation that they should attempt not only to spread his principles abroad but to reduce them to practice: but how seen after his hands were laid low and his influence forgotten did they relapse back with double force upon the world, their own effects a striking proof of their futility and at last remembered, only as an instance of national folly. Martin Luther must have failed to accomplish such a noble revolution in religious affairs unless he had taken upon himself the part of an orator as well as author and forced home his truths upon the attention upon mankind by the irrestable power of his eloquence as well as argument. And again, that masses of mankind are not given to reading, so that were they to take their principles from books individually they might almost be said to be void of principle. Books are handled mostly by men of education and morality who direct to a geat degree what shall be read by the people; consequently, works of an immoral character are rejected. Why is it that a book never has produced a change in the morality of a nation, while the living agent has affected the world? One reason evidently is because there are few books which the community in general will purchase and read, but when their principles are declared publicly, actuated by feelings of natural curiosity, they will listen to them, anxious to acquire without trouble, what they will not labor for. But it may be said that the productions of a genius will descend to future ages and be long exerting an influence: but it is certain, that unless they find men who are willing to labor and exert their influence in their behalf, their effect must be [...] and silent. Let energy, oratory, influence, and destructive principles be combined and they may force their way through the world and carry destruction with them; but laying aside all but the latter, let the principles, however faithfully compiled, be bequeathed to man and few will notice them, less will believe them, and still less be influenced by them. It requires that stimulus which naught but man, fired with zeal in his subject, can give, to enforce any principle upon the mind of men. It is in this that the superority of a sermon, delivered from the lips of its author, consists, over one read by a third person. It is from knowledge of this principle that men who would bring about any great reform in the public mind, employ men whose business it is to present argument and persuasion to reason with the learned to persuade those who have not learned to think for themselves. It is upon that that men can accomplish what books will not, that Colporters are sent through the land with such eminent success. It is from a knowledge of that, that all great reformations have been carried on, that the apostles were sent to the heathens rather than the Bible. It is in vain that Paine closed his Age of Reason with the boast that he had walked through the Bible as a man walks through a wood with an ax, and had felled the trees so that they could never again be made to flourish. He was not aware that it would always require the fire of his eye and the fervor of his genius to give to his doctrine weight and extension. A book has simply one superiority, that it may survive through the ages, but this can never vie with the power which a man exerts, with all his energy talent and influence during a life of three score years and ten directed to one object.

M. W. Grow |

(End of the Milo Grow Letters)