|

Part III of "Being Seen by Rembrandt," copyright © 2001 by Gerald Owen Grow http://www.longleaf.net/ggrow/rembrandt |

|

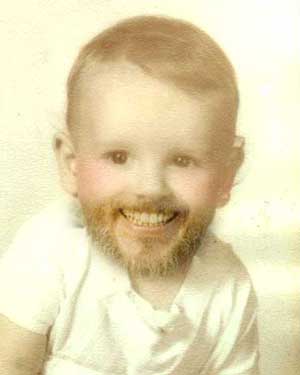

Perhaps it is not so embarassing, then, that an article that started by being about Rembrandt ends by being about me. I wrote this article for no reason other than that, during a week alone the summer of 2001, the one thing I most wanted to do each morning on waking was spend time reflecting on this particular Rembrandt self-portrait. Somehow, Rembrandt became part of my attempt in midlife to reflect on my life and begin to integrate myself. The result, though it uses some of the language of intellectual analysis, is unabashedly personal. I loved being immersed in the depth, seriousness, tragedy, and complexity of Rembrandt's self-portrait, and I loved responding to it with a somber, multifaceted self-portrait of my own. But I found my self-portrait hard to live around. Although deep, it is also narrow. Even in the presence of my mother's excruciating six-year decline into Alzheimer's (which darkened the reflections of this essay), the sprawling, resilient, fortunate comedy of my nature kept provoking me to make additional self-portraits to balance the almost grim seriousness of the first one. I can justify these only by saying that they arose as an irrepressible and inexplicable response to writing this article and that, somehow, they are responses to the intersection of Rembrandt with my life--just as Part I of this article is. Rembrandt, after all, experimented with self-portraits that looked wildly different from one another. These whimsical self-portraits also create expressions that could never have taken place on a person's face. And, like the first portrait, they also integrate widely disparate elements: One integrates two faces across 50 years. The next two integrate faces across species. All three use the same smile. |

|

|

|

|

Gerald Grow at 2 with the beard of 52 This picture anchors my earliest memory--of the man with the large black camera on a tripod, the black cape he hid his head under, and the sudden flash, beside the flowery wallpaper in my grandmother's high-ceilinged living room--as my mother and my aunts looked on, and waved at me, and smiled. In Pearson, in southeast Georgia, in the summer of 1945. (For me, this photo records what the child in it is seeing.)

|

Gerald as Shadow Shadow was a profoundly loyal and loving being, full of sweetness, devotion, sensitivity and delight--qualities her memory helps me celebrate. |

Gerald as Max Max is smart and playful and funny and amazingly focused. His unrelenting efforts to make himself lovable have a tender edge of desperation to them. |

| This led to an ongoing exploration in self-portraiture. Some examples are shown here: | ||

The two faces above courtesy of the Perception Laboratory's Face Transformer.

|

|

|

|

The sense of "being seen by Rembrandt" depends in large part on seeing yourself in Rembrandt -- in the sense that, out of the painting's possibilities, you see reflected back to you the particular emotional gestalt that you are primed to respond to -- either as a reflection of your feelings or as the projected counterpart to them. Wherever we look, we see, in part, ourselves, our possibilities, and our shadows. Perhaps it is only by looking deeply into something else that we can see ourselves. It was inevitable that I would try imagining Rembrandt's self-portrait as my own. This lets me leave the high tragedy of his portrait with a Satyr play, a little dog-dance of those more fortunate than the mythical figure whose worn face we have meditated on. The final illustration brings out the warmth and kindness of Rembrandt's left eye -- the smiling eye -- which is used here unchanged. The less-confident right eye is mine. |

|

|

|

And that leaves me, as I have been throughout this article, sheepishly playing Rembrandt, while Rembrandt plays the king.

[End of Article] |

More on Rembrandt's Self-PortraitsWorking draft of Rembrandt's Standing Self-Portrait in Vienna -- an essay on how the expression in the painting changes as you move close to it. A Self-Portrait Rembrandt Never Painted -- made by combining elements from an early and late self-portrait.

Back to "Being Seen By Rembrandt" <http://www.longleaf.net/ggrow/rembrandt/rembrandt> All original materials on these pages are copyright © 2001 by Gerald Owen Grow. Picture CreditsExcept where noted, historical images come from the Frick Portfolio, ed. by Focarino and Lieber. Photos of the author and the dogs were taken by himself, except for the portrait at age 2 (photographer unknown)

|